A Verily roundtable: Innovating in healthcare with diversity by design

Why it’s so important to approach every part of the medical process — from designing a clinical trial to building an AI-enabled camera — with a focus on equity at the very outset.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease that disproportionately affects individuals of Black African ancestry. They are more likely to get sick and die from the disease, but when a drug to treat SLE called belimumab was approved by the FDA in 2011, the label included a warning for healthcare providers: They should exercise caution in prescribing the product to Black patients. That’s because Black patients were significantly underrepresented in clinical trials for the drug. Belimumab worked in the overall population, but the sub-analysis in the Black population was not statistically significant. Though the cautionary label was eventually removed after a followup study focused on patients who self-identified as Black, these initial warnings led to confusion about whether belimumab should be prescribed to Black patients. The likely result was delayed access to treatment for many of the patients who bear the greatest burden of this disease. Since the belimumab story, underrepresentation of certain populations in drug development has persisted and the FDA recently issued draft guidance to help sponsors plan for the collection and analysis of post-marketing data, a move that highlights the importance of emerging tools like registries and real world data for collecting more and better post-market information for underrepresented groups.

Even though communities of color make up 40 percent of the population they make up roughly 5 percent of participants in clinical trials. The science is far below what it should be.

Vindell Washington, Chief Clinical Officer for Care and Director, Health Equity Center of Excellence

The Speakers

Vindell Washington

Chief Clinical Officer for Care and Director, Health

Equity Center of Excellence, Verily

Caricia Catalani

Head of Design Acceleration,

Verily

Lily Peng

Director of Product Management,

Verily

Guive Balooch

Global Managing Director, Augmented Beauty and

Open Innovation, L’Oréal

Angela Dobes

Vice President, IBD Plexus, Crohn’s & Colitis

Foundation

It’s these kinds of challenges in clinical research that Verily is committed to fixing, and it’s one of the reasons Verily launched its Health Equity Center of Excellence earlier this year. Helmed by Vindell Washington (also Verily’s Chief Clinical Officer for Care), it is not a place or a thing so much as a concept — an organizing principle for the whole company to help better develop solutions that would address inequities in healthcare. One observer likened the Center of Excellence to a catalyst, a way to ensure that things like inclusive trial design happened faster and more smoothly than they had before. Since then, organizations as varied as L’Oréal and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation have collaborated with Verily to use these concepts to design trials and registries that are generalizable, representative, easy to use and operate, and, above all, equitable. To learn more about the different threads that make this kind of ambition possible, we assembled a panel of five people from Verily and two of its partners — the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and L’Oréal. The discussion ranged from why it’s so important to infuse clinical projects and products with an equity mindset at the very beginning and why it’s so difficult to diffuse data throughout the medical system … to what parking lots can tell us about clinical trial design.

Verily: Let’s just get straight at it. Vindell, what’s wrong with healthcare today?

Vindell Washington: After practicing medicine for 25 years, what strikes me most is that there’s a lot of suffering and death that occurs unnecessarily in the healthcare system. If you look at Black communities in particular, Black folks between the ages of 18 and 49 are roughly twice as likely to die of cardiovascular disease as whites, and 60 percent more likely to have diabetes. They’re also twice as likely to die from diabetes. Black American mothers are more than two and a half times more likely to die during childbirth. Women in general have inferior cardiovascular or cardiometabolic care in the US, and they suffer more strokes and heart attacks than they should. That is a tragedy.

What’s the cause of these discrepancies?

Vindell Washington: We’re at a time and place where even though communities of color, for example, make up 40 percent of the population, they make up roughly 5 percent of participants in clinical trials. The science is far below what it should be.

So it’s partially the clinical trials themselves that are to blame?

Vindell Washington: I went into clinical practice at a time when oxygen saturation monitors were introduced widely into the emergency department. Then, we found out 20 years later that if you have brown skin, the monitors don’t work quite as well. In fact, they underestimate oxygenation by a couple of points, which is often enough to determine whether or not you need supplemental oxygen. The problem is that the initial studies around the release of the device did not sufficiently ferret out this difference — likely because of insufficient study diversity. (It turns out the monitors do not work as well on people with darker skin because melanin in skin can interfere with the absorption of light the clip-on devices use to measure the amount of oxygenated blood in a person’s finger.) This is the kind of thing you find out when you have more diverse trials. And so for me, one of the main drivers of disproportionately poor health outcomes among people of color is a lack of diversity in clinical trials, and that equals bad science.

Representative research

Verily: Does that mean that the participants in a clinical trial should reflect the population at large?

Vindell Washington: Every disease has a certain epidemiology. And the epidemiology of the disease should probably match the participants in the trial. If I was studying osteoarthritis, I wouldn’t test my new drug on a bunch of 18 year olds. There’s some nuance there, though: you probably should oversample communities of interest to make sure you have enough power in the study if a certain community is bearing more of the brunt of a disease.

Verily: Why aren’t clinical trials more representative?

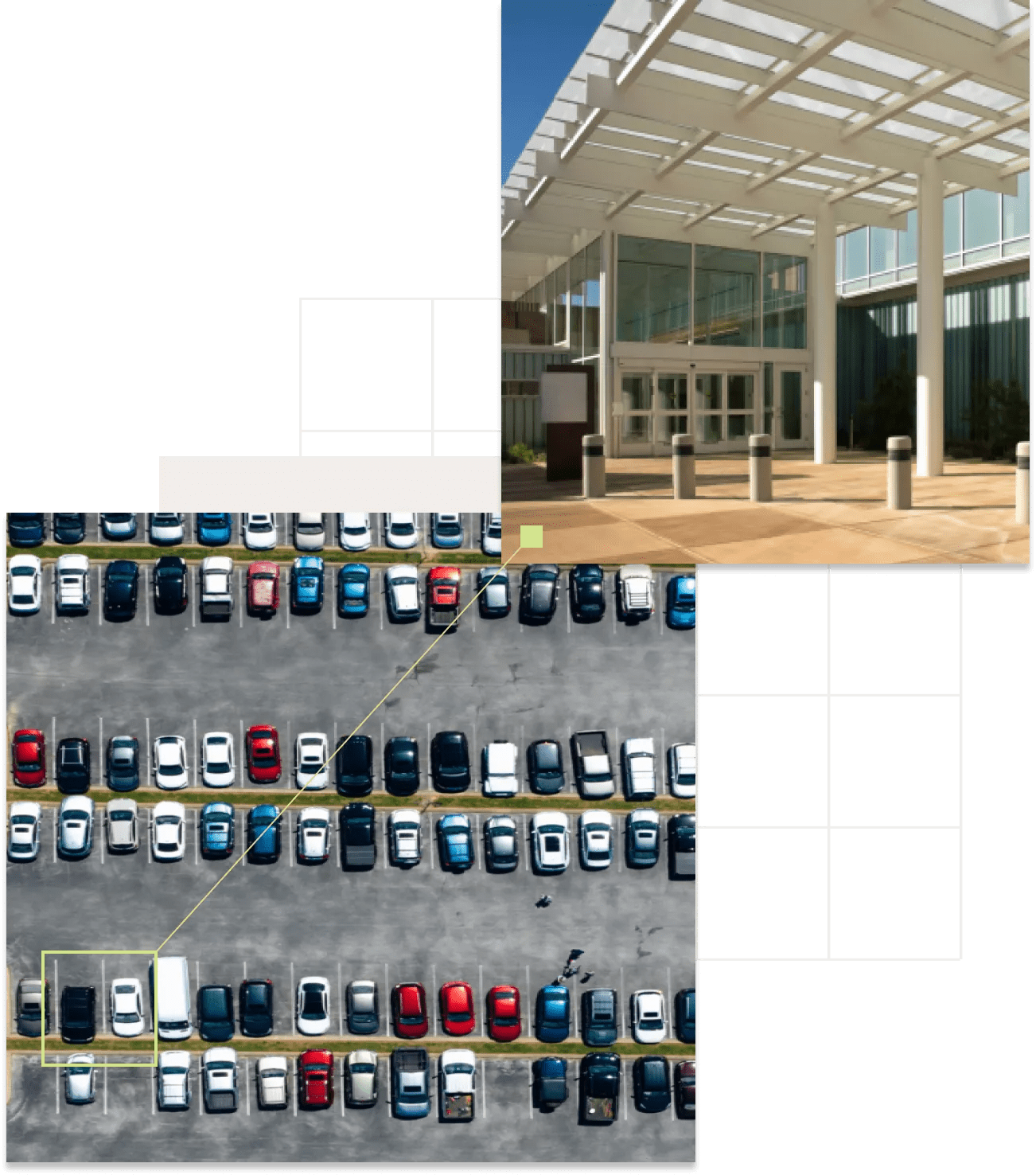

Vindell Washington: Many systems in healthcare are designed for healthcare providers, not patients. I often joke with people: Look at the design of the parking situation at any medical center. Look at where the doctors park and look at where patients park, and work out your steps. Clinical trials are designed around scientific requirements, but the design principles should come from the community or the patients you’re trying to serve. If you are going to design a trial, you need to start with looking at what you’re asking a trial participant to do and then look at how you can make that the easiest path for participants, and the path they’re most likely to follow. Maybe I don’t ask the patient to drive across town or take off work mid-morning on Thursday to come in for a blood draw. Or I make sure that they’re compensated in some way so their time is respected.

And the design principles — the jobs to be done — should come from the community or from the patients you’re trying to serve, as opposed to the other way around, which is designing just for the scientific clinical requirements. It’s a marriage of the two, and designing for the needs of participants leads to success in trial recruitment in communities of concern. And when you make it easy for communities that are on the margins, you make it easy for everyone. The reason that we have cutouts on sidewalks, text messaging, and audiobooks is that the design came about expressly for a community of concern. And in the end, they become something that’s ubiquitous because they make things easier for everyone. That’s part of what we’re pushing from a design structure perspective.

Caricia Catalani: That’s why we are such deep believers in the idea of co-design, bringing the people who would normally just be the targets of our product into that process of designing our product with us. I like to design as if I’m actually in a relationship with the people we hope to serve: how can I be a more loving partner in this process? I think you can do that by listening better, by signaling that you get it. You acknowledge that it’s failed in the past, you acknowledge the feedback people have already given you. And then you ask, Did we do it right? And you come back to it, with humility, over and over again, quickly and iteratively in this fast digital world that we live in, because we’re all impatient to make a difference. That kind of co-design centers our participants in a way that’s not just a motto, but an actual practice.

We have to truly earn the right to ask people for their data, the right to ask people to serve them.

Caricia Catalani, Head of Design Acceleration

What are the key factors to consider when designing a patient-centered product?

Caricia Catalani: I’m the head of our UX design accelerator, which is a team of design specialists who work on making sure that all of our products launch with three things: they are engaging, they’re trustworthy and they’re equitable.

To even be viable, a product needs to be engaging. Healthcare is a thing that people live with throughout their lifetimes. Our aspiration is to follow and support people across months and years of their lives. And from the get-go, it has to be worthy of trust. I think both the health world and the technology world have hurt people’s trust many times in the past, and that is particularly true for communities of color. We have to truly earn the right to ask people for their data, the right to ask people to serve them. And equity — our commitment to designing with equity is why we are here today.

That can be as simple as a typeface — if you are living with three or four chronic diseases, if it’s your second round of chemo, if you’ve had a long day at work looking at your screen, all of these things mean that typeface can enable or disable accessibility to your product.

Part of the problem was that you’re trying to line up a camera with the pupil, which is really tiny. And if you are a person of color, or if you are older, or you have diabetes, your pupil doesn’t dilate very well.

Lily Peng, Director of Product Management

Lily, could you talk about how the ideas Vindell and Caricia are describing impacted the design of the Verily Retinal Camera?

Lily Peng: As with most interesting projects, we arrived at great solutions by a mixture of experimentation and failure. When I was at Google, we wanted to design a camera that could take pictures of the retina to screen for eye disease. We had great AI technology for image recognition, and we wanted to use it to detect diabetic retinopathy, which can cause vision loss or blindness in people with diabetes. We assumed that the camera and the hardware were not going to be a problem, because people were already taking pictures. That assumption was completely wrong: AI depends on being able to capture the great data reliably, across populations, and what we found was that taking pictures that are reliably high enough quality was actually really hard.

Part of the problem was that you’re trying to line up a camera with the pupil, which is really tiny. And if you are a person of color, or if you are older, or you have diabetes, your pupil doesn’t dilate as well, so it’s harder to get a picture of the back of your eye. And so the cameras we had required a skilled operator with a lot of training. But if you’re trying to design for a lower resource setting — people who were in India, in rural areas, in community health centers in the US — just getting the right camera operators was really hard.

We tried a handheld camera, but the camera operator had to hold the camera steady, and patients can have a hard time sitting still. So you had two moving objects, and the shots became even more difficult.

We asked Verily to help us. We said, “We need a camera that is almost self operable.” The team designed what is now the Verily Retinal Camera, which uses something called multi-burst photography. It takes multiple pictures, so you get images of different parts of the retina and you can kind of stitch together the full image. It’s a small, tabletop design, and, with the help of an assistant, the patient can take their own picture.

All of these things that went into the retinal camera were the result of us going to the field, failing multiple times in the design, and then coming back and building something that was usable for the population that we were intending for the camera to be used in.

We are building a cohort of more than 10,000 people that we will run together with Verily — the most inclusive cohort ever for skin health.

Guive Balooch, L’Oréal Global Managing Director, Augmented Beauty and Open Innovation

Guive, I know that L’Oréal has just announced a partnership with Verily that has a camera component. Was camera design an issue you encountered?

Guive Balooch: In our case, with Skin Genius, you have to take a selfie with a smartphone to get diagnostics on your skin and hair. It’s typically something that a lot of people do today, so it’s a gesture that people are very used to. But that being said, if the photo turns out to be blurry, our technology will ask you to retake it. The bigger issue was making sure the diagnostic algorithms work on every ethnic background, which is why we increased our inclusivity on the data capture for different ethnicities and different places around the world.

We are building a cohort of more than 10,000 people that we will run together with Verily — one of the most inclusive cohorts ever for skin health. It will allow us to give people ultra personalized information on their biology and beauty so we can understand even better which products are right for their unique needs.

We rely on Verily’s strong outreach programs to ensure the cohort is as inclusive as the population itself, which is our goal. We have to make sure that we represent everyone, especially in the beauty industry today, where we are very concerned about inclusivity and the ability for every individual to have an understanding of their beauty.

We’ve been pushing on this idea of inclusive beauty for over 10 years now. But we’re not the experts when it comes to running clinical studies. We wanted to partner with Verily because we feel they share the same values that we do around scientific rigor and building a relationship with users.

Vindell, is that where the Health Equity Center of Excellence comes in, to make this kind of study possible?

Vindell Washington: The way the center is positioned, it’s a cross-company element. We can leverage different elements of the company as we try to support our partners like L’Oréal. And so some of the co-design work, the data science group, some of the work on recruitment, some of the toolkits are specifically designed to optimize for equity as well as for speed and efficiency of recruitment.

L’Oréal has a scientific interest in a population that is often underserved by clinical medicine. Often the elements of mistrust and ease of participation that affect the willingness of a potential subject to join a trial for skin health are the same elements that affect their willingness to join a clinical trial. So the goal of the Health Equity Center of Excellence is to listen carefully and to design trials with the communities we hope to serve. That and the proper use of data science maximizes our ability to efficiently enroll members of underserved communities, which is crucial to both efforts.

Guive Balooch: The goal of the Verily / L’Oreal study is multifaceted: We want to understand the exposome- all of the factors that go into skin aging, like pollution, sleep and lifestyle, and its relationship to skin and hair so we can have people foster long-term relationships with their products based on data, not guessing. The study will also educate us so we can develop better, more individualized products. For the past 20 years, we haven’t had a study with more than 100 people over one year; this cohort will provide insights we’ve never had access to before.

Lily Peng: That makes me think of what Caricia said about expressing your care for users through products. That’s a thing that consumer companies like L’Oréal do really well but healthcare struggles with: Designing things with the user in mind that say, “This is how we express care for you. We made it so user friendly because we thought of you from the beginning. You were known to us from the beginning because we went after your pain points.” In the consumer world, we have figured out how to personalize products.

In healthcare, it’s really different. It’s not personal, it feels one size fits all. It comes back to what Vindell was saying about parking lots. Who is at the table when we’re designing these solutions? Who decided that patients with mobility issues can walk this far across the parking lot? No one asked the patient — that’s for sure.

If you’re designing a new lipstick, if the consumer is not happy, you’re not going to build a business whatsoever. In healthcare, though, if something isn’t easy to use, we write a bunch of user guides and make people do a month of training. That is an expression of, “I don’t care about you and your time.” And so we want to get rid of dense training manuals and build things that are just intuitive.

Guive Balooch: Exactly. When you look at how we create products and services in the beauty industry, it’s always been about creating experiences where people feel emotionally attached to the product they use. I think incorporating the ease of use and beautiful designs that you see in consumer products into the medical system and medical technologies like apps and wearables can improve patient experience and engagement: Create something both spectacular and simple that doesn’t compromise safety and accuracy. It’s about blending problem-solving technology with human-centered design.

In my opinion, the patient remains the most underutilized resource in health information systems and evidence generation.

Angela Dobes, Vice President, IBD Plexus at Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation

Contextualizing data

A well-designed registry is a way of caring about patients, of bringing them to the table and better understanding their lives. Angela, can you tell us about the work the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation is doing on that front?

Angela Dobes: In my opinion, the patient remains the most underutilized resource in health information systems and evidence generation. It’s so critical to have methods to collect data on lived experience outside of clinical walls. Chronic diseases like IBD wax and wane. People have a flare, then they feel better, then they have another flare. Let’s say an IBD patient sees their doctor three times a year — how is the disease being monitored the remaining 362 days?

We need advanced data collection methods to close the feedback loop between a treatment and its effect and help patients and clinicians identify the most effective or appropriate treatment. Today, the data being fed into the feedback loop is minimal. We need data that capture a more complete picture of disease and the patient’s lived experience.

Registries and longitudinal studies give us data that not only better reflects the chronic nature of disease but adds better context to the data that’s being collected during clinical care.

What does patient-centered design look like in the context of registries?

Angela Dobes: A registry is not a clinical trial — participants do not receive investigational treatments when participating in registries and prospective longitudinal studies. A registry acts as an infrastructure, an organized system that enables collection of real-world data about a specific population in a standardized format for a specific purpose. Patients play an active role by providing this data — which otherwise is not collected during a clinical trial. As we think about advancements in the registry field, and the acceptance and use of real-world data to generate evidence, we see data about symptoms, like pain and fatigue; wearable data, such as sleep data; diet information and social determinants of health being integrated with data from medical records. Registries can help solve one of healthcare’s biggest problems when it comes to data, which is fragmentation. They connect researchers and healthcare providers, and importantly patients and caregivers, who are all really motivated along this common drive toward better care and better treatments.

Vindell Washington: I don’t know if I can even give as much of a plus one as I want to on the importance of real-world evidence. I want folks to understand that the way that trials are constructed is the opposite of the way that real-world evidence is generated. The crux of a trial is to isolate as many factors as possible to look for a difference in the new thing that you’re introducing. You’re getting more and more narrow, because you’re trying to determine what the effect of this drug or this device is on its own relative to all the other factors.

On the other hand, people don’t live in that study environment, they live in the real world. The very day that that drug is released, it is taken by an individual, not in the isolated study environment, but in their lives. And often, the very folks who are in the most need of help are not the study subjects — but they’re certainly eligible for the treatments post release. So you do need to know what happens in this sort of more complex environment. In the lives that we lead, after the trial, what is the overall effect of the drug? Does it have long-term value; does it drive long-term health?

If you look at where we’ve not had evidence in the past, it’s often been in the post-release period. Being able to make those observations and studies with good longitudinal data is something that Verily is absolutely committed to supporting.

So how do you bring good UX and a consumer tech mindset to medical products and processes?

Lily Peng: I was reading an article that pointed out that you can invent the best technologies in the world, but unless they diffuse across the population, you haven’t really helped people. And the problem in healthcare is that everything exists in silos — we have very low diffusion. And, to Angela’s point, users and participants are the least utilized resource in the diffusion of these kinds of technologies. In the consumer space, you get AI that recognizes cats and dogs, and the next thing you know, it’s on everyone’s phone. Diffusion is fast because that infrastructure is connected. And so the time lag between the haves and have-nots is small.

In healthcare, information exists in silos. The infrastructure is not connected, or sharing is very difficult.

But think about participants helping each other through their Crohn’s disease, and the power of a connected patient community in terms of data sharing, and having your data not only work for you but for other people like you.

So what we want to do is bring in the best of both worlds. There’s really good expertise in healthcare, and there’s really great innovation that happens within the healthcare systems themselves. But we have got to figure out the diffusion piece across populations. If you can have participants say, “Hey, I want to be a part of this,” you can actually accelerate our rate of learning, our rate of diffusion, our rate of innovation. And that’s just a flywheel that will spin faster and faster. But without the participant there, you’re not going to get that.

Vindell Washington: I worked on interoperability as national coordinator for health IT in the Obama administration, and I would add one thing: information exists in silos in part because the incentives for sharing are low among those who have the most control over the data. So as long as hospitals get paid in the way they get paid, until we switch to a scenario where it’s really in their interest to spread information, we’ll be stuck in a scenario where people hoard data. It’s not so much a technology barrier as much as it is a business framework that really inhibits it.

And can you tell us a little bit about why patients are excited to participate in these registries, or as you put it, Lily, these “moments of diffusion.” What will bring them to the table?

Angela Dobes: In the context of IBD, the North Star is definitely cures, and we believe we’re going to get there. But until we do, people want to participate in research to improve their lives and the lives of others. At the Crohn's & Colitis Foundation, you hear patient stories all the time. They make you angry; they make you cry; they’re visceral. But medicine is evidence-based. And all these amazing stories aren’t going into clinical guidelines, so you need the data. And in my opinion, there’s no better way to have your voice heard than by contributing data and having a direct role in research to be able to influence that evidence.

Living with a chronic illness can be stressful and overwhelming, and that’s particularly true for IBD, which is considered an “invisible disease,” with symptoms that you can’t see. That isolation only increases and exacerbates the stressors of living with the disease. But once you find a support system and a care plan that works for you, everything else feels a little more hopeful. We want to keep people in that hopeful state — people want to participate in registries to enable a better tomorrow.

Caricia, how do these kinds of registries fill what you might call a design gap between what’s possible and how things have been done to date?

Caricia Catalani: It’s part of designing a truly participant-centered health experience. There’s a lot of “expert user-itis” in healthcare, where highly trained professionals like physicians, researchers and medical assistants are super-users who collect data on behalf of clinical trial participants — take their blood pressure, take their temperature, take their photographs to observe their skin.

But now, all those things, if done in a way that’s designed equitably, can happen in people’s homes with simple technology. So people don’t have to take a day off of work — they don’t have to go to the parking lot at all. That makes it so much more accessible and equitable for people in any part of the country to participate in a registry or a clinical trial.

That’s part of design that Verily is excited to enable. It’s a really radical moment to be a part of.