How digital biomarkers could transform evidence generation

Data collected in the clinic doesn’t capture how patients actually live and respond to therapies in real time. Wearables like Verily’s are part of the real-word data revolution.

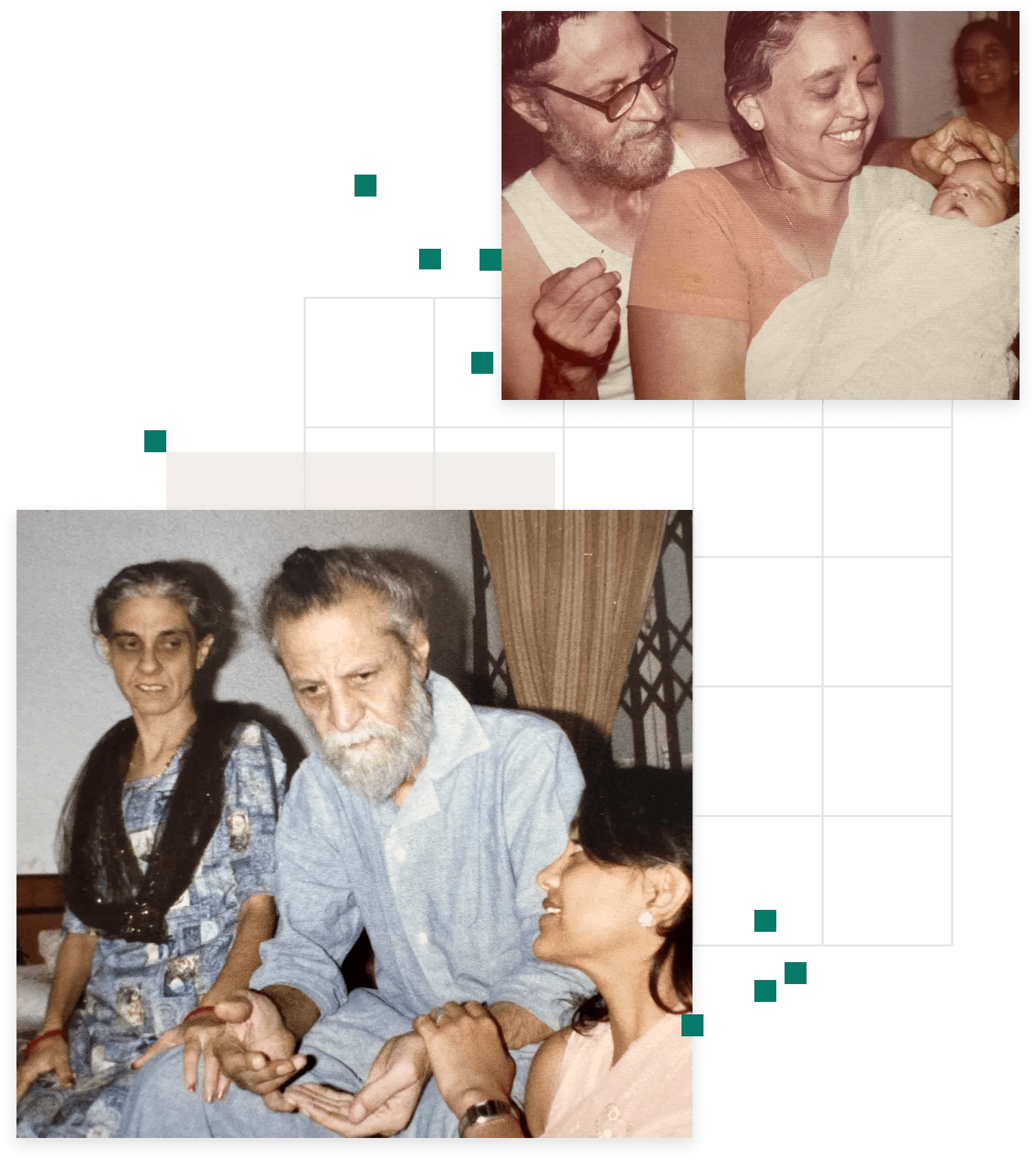

Ritu Kapur sat in her car in the Verily parking lot, straining to hear what the doctor was saying. She had gotten there early so she could focus and pay attention to the call before heading in to work. The conversation filtered from her aunt’s tiny phone mic at the doctor’s office in Chicago through the speaker system in her RAV-4, beat up from years of parking on San Francisco streets.

Her uncle had been slowing down over the last few years, becoming forgetful and unsteady on his feet. Was it Parkinson’s disease? Alzheimer’s? Something else? The family was trying to get a clear diagnosis so they’d know how best to care for him, but it had been difficult. The latest hunch was that there was too much pressure on his brain, and a few days earlier, the care team had performed a procedure to alleviate it temporarily. The family was gathered to see if the procedure had been helpful enough to indicate that brain surgery would be an effective next step.

Kapur, the Head of Digital Biomarkers at Verily, got her Ph.D. in neuroscience after seeing her grandfather suffer from Parkinson’s; now she wanted to be there for her uncle, who was declining in ways that seemed both similar and different. But she was frustrated by medicine’s limited ability to diagnose or measure neurodegenerative disease.

Was he sleeping better, the doctor asked? “I think so, maybe a little bit,” he said, “No,” said his wife. “It’s not better. You were waking up, even last night.” Was it easier for him to get up from a chair since his previous visit? The doctor conducted a brief movement analysis. “Try to stand up without using your hands on the arm rest… Hold your arms straight out… Walk for me,” said the doctor. “Hrm, I think that’s a little better, but I’m not really sure.”

“I was sitting there, and I could hear them trying to figure out if it was better now than it was before. And I was like, frankly, this is garbage,” recalls Kapur of the episode in early 2018. “We can measure this. We have to do something about this."

So she took it to her team, and they did.

We can extract information from those sensors and start to relate it to our health and our well being. There's a whole science that needs to come to fruition, and that's what we are building here.

Ritu Kapur, Head of Digital Biomarkers

Ritu at the Verily Numetric Watch hardware lab

Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative brain disorder that causes tremors, lack of coordination, and difficulty speaking and walking. Many drugs are available to diminish these symptoms, but there is no treatment that can reverse the progression. Another problem: There’s no objective way to measure that progression, which makes it hard to tell if disease-modifying drugs are working. This is especially tough because you want to stop disease progression as early as possible. “We need to detect subtle changes,” Kapur says. “But we also need to be confident that they are real.”

In most studies, patients self-report symptoms and then researchers evaluate patients in the lab. However, this paints an incomplete picture — it can be difficult for patients to accurately self-report (it’s hard to say how well you slept, for example). Plus, symptoms can either be too subtle for doctors to observe or may actually appear worse in a stressful clinical setting.

“Stress can elevate certain hormones and lead to more motor symptoms,” says Jovelle Fernandez, a physician and Verily collaborator. “But, in real life, is that really happening? Or is that only evident during that observation period? The industry needs decision-grade data that capture real world experiences.” Without real data collected consistently, it can be difficult for both the patient and the doctor to determine if symptoms are better or worse.

Kapur joined Verily in 2017 to help build Verily’s neurology platform. Her first major study, the Personalized Parkinson Project, used the Verily Study Watch (also referred to as “the watch”), a sensor-based wearable device that can provide non-invasive, continuous monitoring of a person’s physiology and behavior, such as their heart rate and patterns of activity throughout the day. Today, more than a thousand patients with Parkinson’s disease have worn the device as part of clinical trials. Kapur leads the Digital Biomarkers team, and the Verily Study Watch is their flagship device.

Patients can engage with the watch to take a virtual motor exam that measures symptoms like tremor; they can also collect ECG readouts, log when they take their meds and tell researchers how intense they think their symptoms are.

Ritu Kapur, Head of Digital Biomarkers

At first glance, the Verily Study Watch looks like a basic smart watch: an e-ink face tells the time and date, and the straps come in a variety of colors. But behind the scenes, it’s collecting biometric data around walking behavior and motor control. The watch can also monitor heart rate signals, which can be used to measure sleep and other functions of the unconscious (“autonomic”) nervous system, which are also affected in people with Parkinson’s. Patients can engage with the watch to take a virtual motor exam that measures symptoms like tremor; they can also collect ECG readouts, log when they take their meds and tell researchers how intense they think their symptoms are.

The collected data are encrypted and uploaded to the cloud, and that information helps researchers and clinicians understand how Parkinson’s symptoms change over time and in response to medication. Kapur hopes that these digital biomarkers will be translated into data that are useful for doctors monitoring their patients. “It's about understanding what the patients really need and coming up with a solution that will be there in the long term to provide value to patient care, the necessary information to the health care providers, and then, ultimately, quality of life for the patients,” Fernandez says.

These data could also provide important insights in the context of pharmaceutical trials. “Decisions by the FDA about how products are used or approved are made based on evidence,” says Joe Franklin, Head of Strategic Affairs for Verily. “That evidence is limited by the tools used to collect it. Unless we develop tools to collect evidence about the real-world, daily experience of patients, this information won’t be available to inform FDA decisions, or care more broadly.”

Verily Study Watch is part of a movement toward a new paradigm of continuous evidence generation — collecting tons of relevant data at all times. These longitudinal data were previously impossible to accurately collect in real-world settings, but, used properly, could accelerate clinical research, better tailor health care for individuals, and help improve treatment decisions.

The Verily team has worked with patients ranging in age and physical ability, including those with mild to severe Parkinson’s disease. “It turns out that almost everybody can put on a watch,” Kapur says. So far, Verily has used the Verily Study Watch for Parkinson’s studies on drug efficacy, motor function and disease progression. Plus, it has been used by independent researchers, including in a 2023 mental health study where researchers found that the signals from the watch could assess pain, sleep quality and anxiety for those with traumatic stress.

Everyday data about trial participants could transform research evaluation as well as the lives of patients with Parkinson’s, closing the gap between the daily symptoms that patients experience and the clinical research that can extend and improve their lives

Ritu in conversation with long time collaborator, Head of Sensors and Data Science, Erin Rainaldi

Earlier in her career, Kapur worked as a neuroscientist and electrophysiologist at a medical device company, where she helped develop an implantable neurostimulator for patients with epilepsy. The implant delivered small brain stimulations which, over time, decreased the frequency of seizures. But it was difficult to quantify the effect.

First, because many seizures happened while they slept at night, the participants couldn’t accurately provide a seizure count. What’s more, “when people are talking about their seizures, and whether they got better or worse with the device, it wasn't just about their seizure counts,” Kapur said. Sometimes the difference was in the severity of the seizure — rather than losing consciousness in public, perhaps the patient would simply turn their head and sneeze. At other times, the difference wasn’t in the seizure count but, rather, improved quality of sleep and lessened fatigue. These were the changes that were deeply important to patients’ quality of life, but, Kapur says, “none of this was captured, all of this was lost to the vagaries of what the clinical endpoint evaluated.”

The FDA does use some real-world data like these as part of the drug approval and monitoring process. New advances in technology have heightened the Agency’s focus, and regulatory support for technology like the Verily Study Watch has been building. “The FDA and others are eager to have scalable solutions for understanding how drugs work in routine care settings,” Franklin says, and improving evidence generation has been named as a top priority by FDA commissioner Robert Califf. In 2021, the FDA issued a draft guidance outlining how to use real-world data in clinical studies by evaluating and documenting data quality, linking datasets and by organizing data collection in prospective registries to support regulatory decision making. The FDA also published a framework earlier this year to guide the use of data derived from digital health tools like the Verily Study Watch in regulatory decision-making for drugs and biological products. The European Medicines Agency issued a similar framework in 2022.

“The FDA is in the middle of a really important era of progress when it comes to expanding the types of data that can be reviewed in a submission for drug or device approval,” Franklin says. “So what we're focused on at Verily is understanding how to line up the data in a way that is going to be able to be reviewed confidently by the FDA.” Enter the Verily Study Watch.

The watch is part of a new wave of digital health tools, a category that encompasses wearables, implantable devices, ingestible sensors, sensors in the home, and phone apps. “We can extract information from those sensors and start to relate it to our health and our well being,” Kapur says. “There's a whole science that needs to come to fruition, and that's what we are building here.” One of Verily’s goals is to develop both the technology and methods for storing and deciphering the data that tech collects to make this future possible.

So far, the Verily Study Watch has been deployed in studies in the U.S., the Netherlands, and Japan. Throughout this research, Verily has focused on recruiting a wide, diverse testing population. “Everybody's experience of disease is very different, which is why capturing a holistic and diverse population is so important,” says Kapur.

Verily’s mission with this project and others, such as its recently announced registries for longitudinal data, is to not only collect data on a large scale, but also make it easier for participants to partner in clinical research. “How do you make it possible to conduct research in a wider variety of sites, in a wide array of patients who are geographically diverse and demographically diverse?” Franklin says. “How do you lower the costs that research imposes on the overall system by making it easier to collect certain types of data?” Wearables like the Verily Study Watch could be part of the answer. The watch can capture data from all kinds of patients, so that even those who aren’t close to medical centers can participate in trials.

The results of the Verily Study Watch have been promising. For example, in a 2022 study published by Nature, Kapur and her team tested the watch on patients with early Parkinson’s disease for more than a year. In that time, they demonstrated that the watch’s weekly measurements from the motor function tests gave a reliable picture of the disease’s severity and, what’s more, that the snapshot of symptoms seen in the clinic wasn’t always representative of what was going on in a person’s daily life.

How do you make it possible to conduct research in a wider variety of sites, in a wide array of patients who are geographically diverse and demographically diverse?

Joe Franklin, Head of Strategic Affairs

Another study in Japan, to which Kapur and Jovelle Fernandez both contributed, focused on whether the Verily Study Watch could accurately detect changes in symptoms as patients received an IV pharmaceutical treatment in a hospital setting. “It's relatable to patients because they use it like a regular watch,” Fernandez says. Physicians also found it easy to explain to patients how to use it. As such, “Usage was very high.” The results of the study were overwhelmingly positive, finding that the device accurately detected symptoms and the impact that drugs had on them.

Now that data have been collected from thousands of patients, the team is starting to consider how the biomarkers collected from the Verily Study Watch can improve everyday patient care. “Pragmatically, you can put a watch on someone, but what happens to the information?” Kapur says. People with Parkinson’s say that they want to be partners in decision-making around their care, and tools like these could help drive conversations about what’s working or not working for that patient. This input can, in turn inform drug developers, regulators and healthcare providers about what measurements are most meaningful to patients, in the context of their daily lives. As FDA and other regulators have emphasized, a confident understanding of what matters to patients is an important step in patient-focused drug development and the use of patient-centered outcomes in regulatory decision making.

Still, Kapur hopes that the Verily Study Watch trials can bring everything full circle and deliver what current patients need. Though Parkinson’s may not be cured in the participants’ lifetimes, they don’t just engage in these trials to help themselves. “People do this because they're trying to make it better for future people living with Parkinson’s,” Kapur says. “They're paying it forward, and it's amazing.”

Recently, Kapur went to the Netherlands, where she was able to shadow some clinic visits for trial participants. For one patient, it was his final visit in the trial, and it was time to give the Verily Study Watch back. Unlike many consumer wearables, this device had no exciting apps — it doesn’t play music or display text messages. Just the date and time, a medication log and periodic reminders to take a virtual motor exam. Still, the patient said he would miss it for its elegant design. “It’s a beautiful watch,” he said. “I feel a little bit sad that I have to give this back.”

It was, Kapur says, “One of the best compliments they could have received.”