Introducing FHIR-AgentBench: A new standard for safe, trustworthy Health AI

Healthcare is rapidly standardizing on FHIR and accelerating the development of LLM-based health agents, yet the industry still lacks a realistic, public way to measure whether these models can retrieve and reason over actual FHIR data. Verily created FHIR-AgentBench, a new benchmark that establishes the standard for accuracy and safety required to build and deploy safer, more reliable health AI systems.

Why we need a FHIR-based

benchmark for clinical Q&A

The healthcare sector is converging on the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard, driven by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) mandates for FHIR APIs and widespread adoption by major EHR vendors. Concurrently, the development of Large Language Model (LLM) applications for Electronic Health Record (EHR) question-answering is accelerating, seen in innovations like Google's Personal Health Agent.

Verily has been a proactive leader in both of these emerging trends. On the infrastructure side, we use FHIRPath to enable seamless collaboration between teams and to validate FHIR data quality holistically. On the user experience side, we recently launched Verily Me to help participants understand and navigate their health data with an AI-first mindset.

However, despite the explosion of LLM agents designed to interpret health data, the benchmarks required to evaluate them have lagged behind these interoperability trends. The industry faces a distinct lack of realistic, extensive, and public benchmarks that assess an LLM’s ability to retrieve and reason over FHIR-structured data. To build agents that are truly safe and useful for patients, we needed a measuring stick that specifically tests interaction with the reality of FHIR.

FHIR-AgentBench: An open-

source benchmark for FHIR-

based Q&A

To address this gap, Verily partnered with the Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology (KAIST) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to create FHIR-AgentBench. This benchmark is designed to integrate three key components for FHIR-based EHR question answering: real clinical questions, complex patient FHIR records, and mapping of ground-truth FHIR resources.

We extensively evaluated LLM agents against this benchmark, systematically comparing five agentic architectures on retrieval quality and answer correctness. Our contribution has been recognized by the academic community with a paper acceptance at the Machine Learning for Healthcare (ML4H) conference, and we’re committed to open science: the paper is available on arXiv, and the dataset, agent evaluation, and corresponding implementations are all publicly available on GitHub.

FHIR-AgentBench by the

Numbers

FHIR-AgentBench stands out as a unique dataset grounded in real patient data with FHIR-specific Q&A. Crucially, it is the only publicly accessible dataset that enables the simultaneous evaluation of retrieval precision, retrieval recall, and answer correctness using real clinician questions on FHIR data.

Some of the key statistics of FHIR-AgentBench include:

- ~3,000 Question-Answer-SQL-FHIR resource pairs

- 80 different question templates

- ~100 distinct patients

- 43,000+ total FHIR records

- 15 unique FHIR resource types

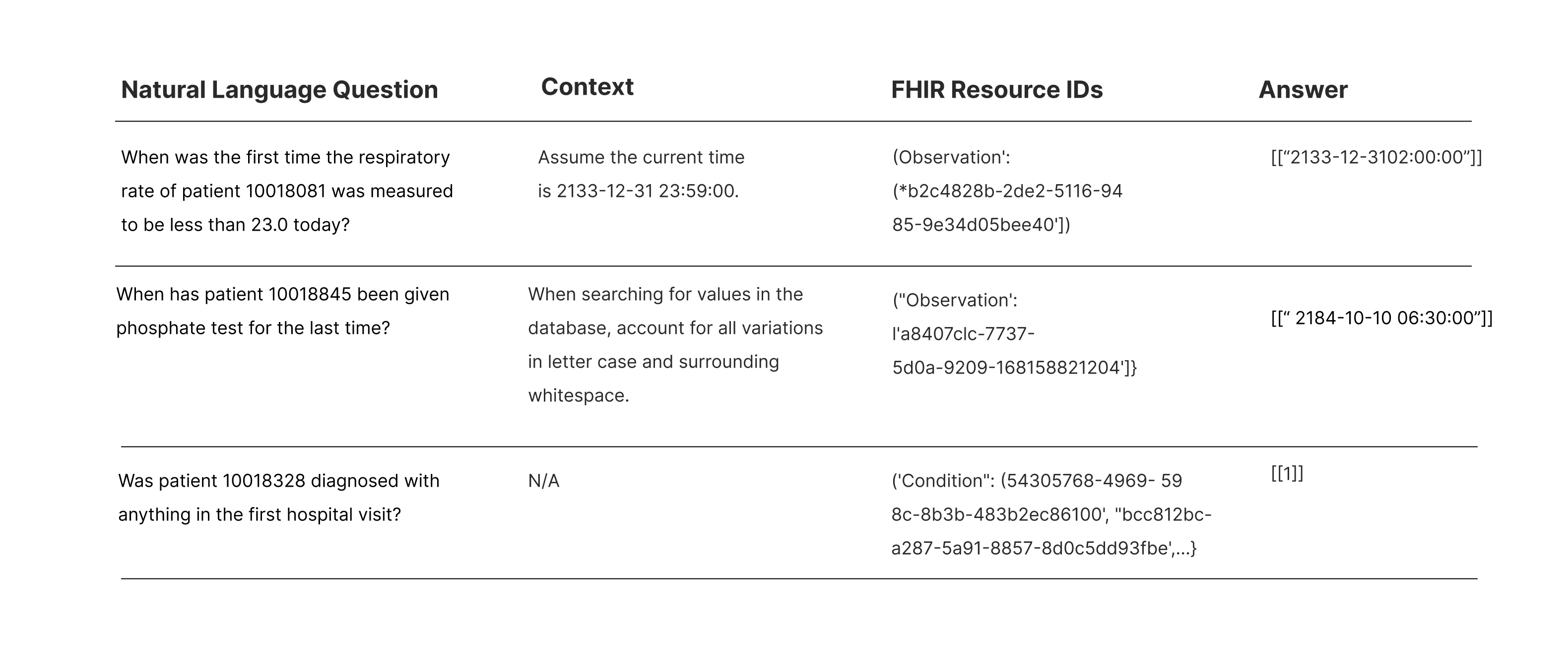

A sample of the dataset is shown below:

Table 1: Sample data in FHIR-AgentBench.

Technical deep dive —

constructing FHIR-

AgentBench

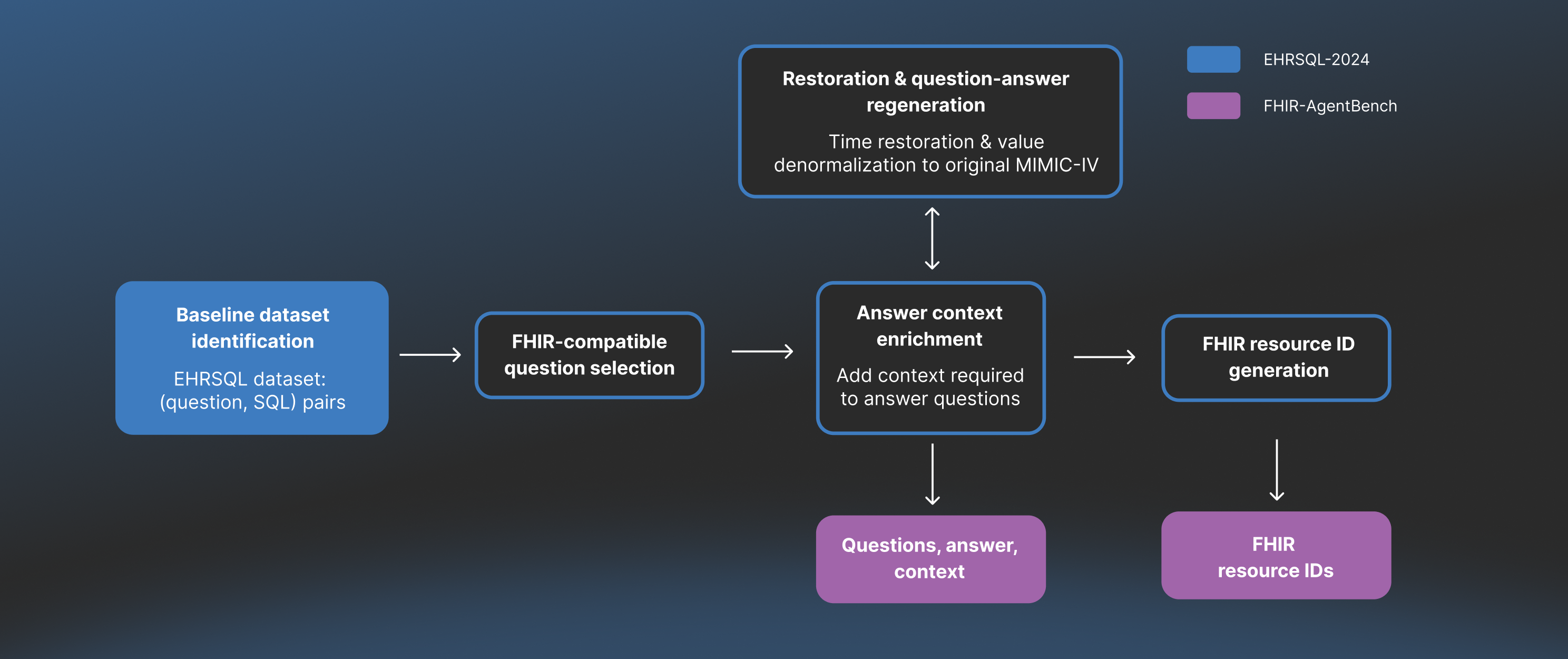

Constructing a benchmark that accurately reflects the "messiness" of real-world clinical data required a rigorous data engineering pipeline. The process involved identifying a real clinical dataset, reverse-engineering complexity to reflect real-world conditions, and finally integrating the FHIR component. The specific steps are outlined in the figure below.

Figure 1: FHIR-AgentBench dataset construction process.

1. Baseline dataset identification

We started by leveraging the EHRSQL dataset, which contains ~7.5k question-SQL pairs published by KAIST, our academic research partner. To understand this baseline dataset and the construction process of FHIR-AgentBench, it is helpful to define the underlying datasets:

- EHRSQL: Dataset that was originally designed for Text-to-SQL tasks built on top of MIMIC-IV-Demo. This dataset contains real clinical questions and corresponding SQL queries on top of MIMIC-IV-Demo to answer those questions. While useful as a starting point, the data in EHRSQL is heavily normalized and processed - stripped away of the complexity we need to develop our FHIR-based benchmark.

- MIMIC-IV-Demo: A small, openly available subset of the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database, which is a database of ICU patients from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center curated by MIT. It contains de-identified electronic health record (EHR) data for 100 patients.

- MIMIC-IV-FHIR-Demo: The FHIR version of MIMIC-IV-Demo data, converted into the HL7 FHIR format by MIT.

2. FHIR-compatible question selection

Our first step was identifying questions unanswerable using FHIR. Specifically, we excluded questions relying on SQL tables or attributes that do not map to the MIMIC-IV-FHIR-Demo standard. This left us with a focused set of 2,931 questions where the answers could be definitively found within a FHIR resource.

3. The "De-Normalization" process: Because EHRSQL uses its own processed version of MIMIC-IV, we could not use its queries directly to test against standard FHIR data. We needed to "undo" the processing EHRSQL performed and harmonize the data elements back to the raw MIMIC-IV-Demo state. The “De-Normalization” step involved two sub-processes: 1) Restoration & Question-Answer Regeneration, and 2) Answer Context Enrichment.

Restoration & question-answer generation

We modified the EHRSQL questions and SQL queries, accounting for the following de-normalization steps:

- Time-shifting: This step modified the questions and SQL queries to restore each patient's specific "anchor year," ensuring varied date ranges and relevant data when re-running queries on the MIMIC-IV-Demo tables.

- Restoring raw values: Normalized text values from the SQL dataset (e.g., "lorazepam") were mapped back to their original, "noisy" formats in the raw FHIR data (e.g., "LORazepam") to better reflect real-world data variability.

- Contextual validation: Minimal required context was manually curated and injected as guidance into the benchmark, helping LLM agents answer complex questions that were otherwise impossible due to a lack of implied knowledge in the database schema.

4. FHIR resource ID generation

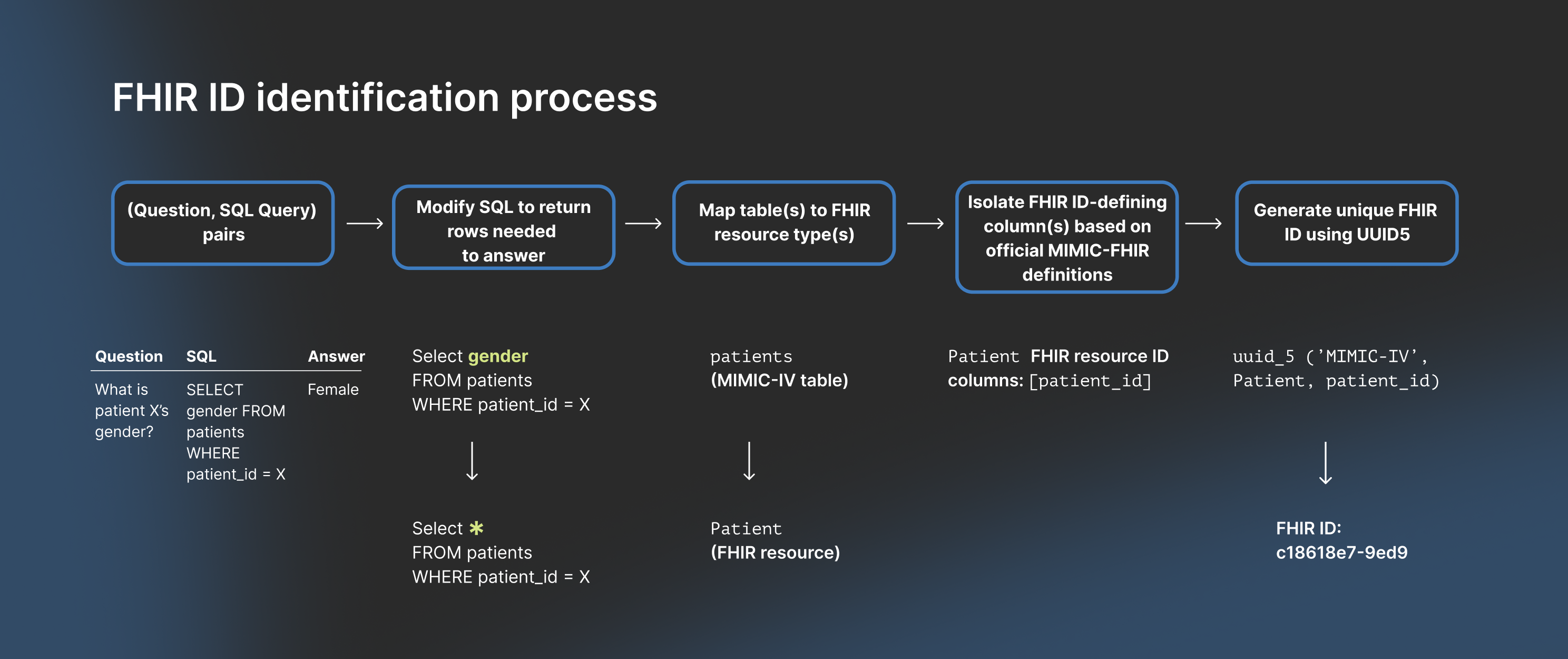

Finally, we needed to identify the ground-truth FHIR resource IDs required to answer each question. To do this, we modified the SQL queries to return the specific rows containing the answer. We then mapped those rows to the official MIMIC-IV-FHIR resource types and used UUID5 conversions to generate the unique FHIR resource IDs for every question. An illustration of the process is depicted in the following figure:

Figure 2: Ground truth FHIR resource ID generation process.

Through this rigorous data engineering process, we constructed FHIR-AgentBench – a FHIR-based benchmark dataset which enables a comprehensive test of retrieval and answer correctness performance of EHR question-answering applications.

Performance of baseline LLM

Agents against FHIR-

AgentBench

With FHIR-AgentBench established as a rigorous standard, the immediate question was: How do baseline LLM agents perform?

To answer this, we tested various agentic architectures and their performance on the following three core metrics:

- Retrieval Precision: “What % of the retrieved FHIR resources were actually required to answer the question?”

- Retrieval Recall: “What % of FHIR resources required to answer the question were actually retrieved?”

- Answer Correctness: “Was our LLM agent’s answer correct?”

Agentic architectures

The agentic architectures were constructed using a combination of building blocks, and interaction patterns.

The three core building blocks consisted of data retrieval and analysis functions that LLM agents could call via tool-calling:

- FHIR query generator: Allowing agents to write raw API query strings (e.g., Observation?patient=XXX&code=YYY).

- Retriever: A pre-defined toolset where the agent requests resources by type or ID.

- Code interpreter: Allowing the agent to write and execute Python code to process the data.

The interaction patterns consisted of the way in which agents can reason and output the answer:

- Single-turn: Agent retrieves and answers in one go

- Multi-turn: Agent can iteratively reason and act, allowing it to refine its search or perform multi-step analysis patterns.

The final 5 architectures built using the combination of building blocks and interaction patterns were the following:

- Single turn LLM + FHIR Query Generator

- Single-turn LLM + Retriever

- Single-turn LLM + Retriever + Code

- Multi-turn + Retriever

- Multi-turn + Retriever + Code

These agentic architectures were tested with both closed and open-source underlying base models: o4-mini, Gemini-2.5-flash, Qwen-3, and LLaMA-3.3.

Results: A ceiling on performance

The results revealed a stark reality: FHIR-AgentBench is a difficult benchmark under baseline agentic architectures.

Even the best-performing architecture, which was Multi-turn + Retriever + Code using o4-mini, capped out at only 50% answer correctness, with 68% retrieval recall and 35% retrieval precision.

Our analysis highlighted clear trade-offs in agent design:

- Code improves reasoning: Architectures equipped with a Code Interpreter consistently achieved higher answer correctness, as they could programmatically filter and aggregate data rather than relying solely on the LLM's context window.

- Multi-turn improves recall (at a cost): Allowing agents to iterate (Multi-turn) helped them dig deeper and find more relevant records (higher recall), but they often became distracted by irrelevant data, lowering their precision.

- Architecture > model: Interestingly, our ablation studies showed no clear performance trends based on the base model choice.

Why LLM agents fail – the

structure of FHIR

The failure modes were rarely simple hallucinations; they were primarily related to difficulties in navigating the structural complexities of the FHIR standard. We identified three primary failure categories:

- The mapping problem - Misidentifying resource types: Agents often struggle to map clinical concepts to the correct FHIR resource, frequently querying the wrong resource (e.g., Procedure instead of Observation for "ostomy output").

- The specificity trap - Over-constrained queries: Agents generate overly precise query strings (e.g., using a single LOINC code for "respiratory rate") that are too narrow and fail to retrieve data stored under related, multiple codes.

- The reference problem - Navigating multi-hop Links: Agents fail to traverse the graph of linked FHIR resources, meaning they retrieve a resource (e.g., MedicationRequest) but fail to follow its reference ID to the necessary secondary resource (e.g., Medication) to get the final answer. Ultimately, these failure modes demonstrated that general-purpose agentic architectures hit a ceiling when facing the intricate, graph-like structure of FHIR data. With the best agentic performance capped at 50% answer correctness and no differentiability across baseline model choice, it was clear that simply scaling up the model wouldn't solve the problem.

Verily’s FHIR agent: A self-

reasoning framework for

continuous improvement

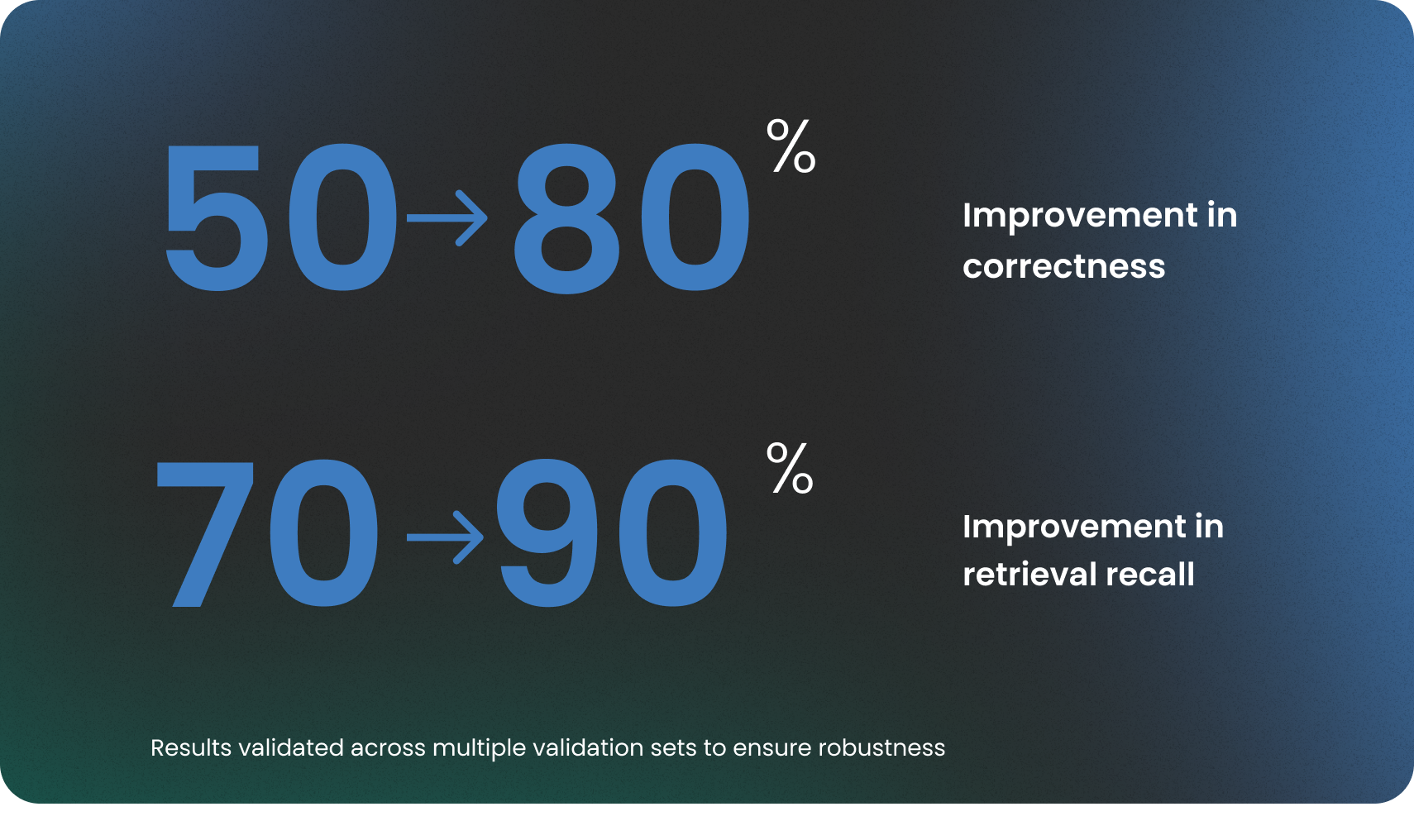

To address the 50% performance limit of baseline architectures, we utilized a purpose-built, automated self-improvement agentic framework to significantly improve FHIR-based Q&A capabilities. This approach allowed agents to continuously learn and optimize their reasoning based on observed failure patterns from the FHIR-AgentBench. By combining deep domain knowledge with this automated optimization, we achieved a critical lift, boosting the agent's answer correctness from 50% to an industry-leading 80%, and retrieval recall from 70% to 90%. This specialized, self-tunable agent performs markedly better in handling the complexities of FHIR data.

Integrating our findings into

Verily Me

The creation of FHIR-AgentBench and the optimization of our FHIR Agent were not just academic exercises; they were driven by Verily’s mission to bring precision health to everyone, every day.

The core components and architectural insights derived from this high-performance agent are currently being integrated into the next iteration of Verily Me — our consumer app made to provide personalized care recommendations and insights. We’re moving from a static to a dynamic, intelligent system capable of navigating the complexities of FHIR data with high fidelity.

This evolution will power the Verily Me experience, allowing us to deliver on our promise of helping participants not just view their health data, but truly understand it.

A new standard for health AI

As healthcare moves toward fully interoperable, FHIR-native data ecosystems, the next generation of AI systems must be held to a higher standard of accuracy, reliability, and clinical safety. Meeting this responsibility requires evaluation tools that reflect the real structure, nuance, and stakes of modern healthcare data.

With FHIR-AgentBench, we have taken an important step toward that future. We have established a new standard for reliability, created a practical way to de-risk AI in high-stakes environments like healthcare, and strengthened the industry’s commitment to interoperability and FHIR adoption.

We invite researchers, developers, and healthcare organizations to use this benchmark to test their models and contribute to its evolution.

Explore FHIR-AgentBench: You can access the paper on arXiv, and the dataset, construction pipeline, and baseline models on our GitHub repository.